“So if you love me,/ love me everywhere”: Place, Love, and H.D.’s Eternal Space-Time

My dissertation on H.D., the modernist poet. Also presented at the 2025 American Literature Association Conference in Boston.

All photos borrowed from Yale Beinecke Special Manuscript Library.

Introduction

‘That pure representation of homogenous objects – the night in serenity, a limpid little wall, the provincial scent of honeysuckle, the elemental earth - is not merely identical to the one present on that corner so many years ago; it is, without resemblances or repetitions, the very same. Time, if we can intuitively grasp such an identity, is a delusion.’

-Jorges Luis Borges

Histories and canons are stories that privilege those in power, and H.D., a poet and author who lived through two world wars, was largely written out of the male-dominated canon or read solely through her relationship with men. But H.D.’s story is much more complex than the various ‘men of 1914’ who she associated with. Her works are as variegated and multiple as the times and places they respond to, shifting between poetry, autofictive novels, translations, epics, and films. Despite the complexity of her prolific additions to the twentieth century, H.D. continues to be restricted by Ezra Pound’s description of her as the ‘Imagiste’. H.D. has only recently gained traction beyond that in late 20th century feminist and queer theory through scholars like Susan Friedman, Diana Collecott and Eileen Gregory. But Lawrence Rainey, a recent scholar of modernism, minimizes H.D. as a minor ‘coterie poet’ who had been inflated by feminist bias. H.D. is still relatively excluded from the canon; in particular, her prose works are near impossible to locate.

This dissertation will largely be looking at her prose works, many of which are unpublished, minimally published, or in archives. Many of the novels that will be discussed are obliquely referential to her own life, and thus the inclusion of biographical aspects of H.D.’s life in this dissertation is not meant to undervalue her craft; rather, her novels are woven into a dialectic tapestry with her life and biographical information is integral to any discussion of her work. Born in America, she met Ezra Pound in high school and was briefly engaged to him, which led to her move to Europe where she became involved with modernist literary culture and Imagist poetry. While in England, she married another poet, Richard Aldington. Their marriage was creatively productive, but disintegrated when Aldington was sent to fight in the First World War. Just as the Lusitania was sunk by German U-boats, H.D. miscarried their child. Marital infidelity on both sides confirmed the end of their marriage, and H.D. became pregnant again as the war ended. Suddenly alone, H.D. had contracted influenza while pregnant through another man, and doctors told her that only she or the baby would survive. In a seedy hospital in a benumbed post-war London, H.D. was in the lowest period of her life.

It was at this point when H.D. met her life-long lover, Bryher, a writer and explorer who supported many modernist projects from her family’s ship-owning wealth. Bryher carried ‘the material and spiritual burden of pulling’ H.D. out of her despair, and ‘anyone who knows [H.D.] knows who this person is [...] we all call her Bryher’. Born Annie Winifred Ellerman, she had renamed herself Bryher after one of the wildest islands of England’s Isles of Scilly. Bryher brought H.D. back to health and vowed to see ‘that the baby was protected’ and ‘cherished’. Though they each had various other lovers, H.D. and Bryher remained intimately tangled for the rest of their lives. Together, they traveled, made films, raised a child, and endlessly wrote about each other through the guise of changed names and settings.

Another promise Bryher made to H.D. in their first year together was that she would take H.D. to ‘to the land, spiritually of [H.D.’s] predilection, geographically of [her] dreams’. This idea of travel to ‘the land’ is central to this dissertation, as it is through H.D.’s literary depiction of place and spatiality, or what is called today the movements of ‘materialism’ or ‘physicalism’, that H.D. cultivates what this dissertation will come to call her eternal space-time. In the Newtonian separation of space from time there has been a bias towards the discussion of time and a marginalizing of ideas of space. Similarly, while H.D.’s warping of time has been talked about, the intersection between time and space in H.D.’s work lacks critical attention. More broadly, time has been associated with ‘masculine’ connotations like ‘History, Progress, [and] Civilization’, whereas space is feminized and aligned with concepts such as ‘nostalgia, emotion, aesthetics, [and] the body’. Not only does H.D. revere the presence, power, and permanence of space (and its connotations), but she refuses the binarizing dichotomy between space and time. Rather, she creates a holistic space-time in her works, in dialogue with Einstein’s theories of relativity and the idea that ‘[n]o-one has yet observed a place except at a time, nor yet a time except at a place’.

Though H.D.’s space-time is out of sync with forward moving linear time, her temporality is not lacking or abstract but is instead a tactile temporality of plenitude. In her texts, she links at once a variety of places and times, thus foregoing singularity and inviting accumulation and collectivity. In its forsaking of linearity and essentialism, her temporality is queer. The definition of queer time is appropriately unfixed in its definition, varying across scholars. Valery Rohy posits queer time as resisting the ‘regular, linear and unidirectional qualities of ‘straight time’. Meanwhile, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick proposes that ‘queer is a continuing moment’. Carolyn Dinshaw merges queer time with space in her definition of queer temporality, which she envisions as ‘forms of desirous, embodied being[s] that are out of sync with the ordinarily linear measurements of everyday life’. H.D. similarly elides simple definition in her creation of her queer space-time. This dissertation will embrace the perpetually fluid and indetermined understandings of her philosophies, an appropriately queer approach.

While her queer space-time is difficult to pin down, the temporality that she is resisting prides itself on being definable. The definitive and defining nature of normative linear clock-time is at one with capitalist ideals of perpetual forward progress and imperialistic development. These temporal regimes are central to sustaining power structures of Western society, defining and securing who is normative and who is not. Specific to H.D., the modernist privileging of the ‘Now!’ often urged a dangerously infinite sense of ‘growth’ that led to fascist movements, as well as a harsh demarcation of what was passé. Modernism’s shiny view of the present did not include everyone, but very often propagated violent and marginalizing ideas. F.T. Marinetti in his Futurist Manifesto aimed to ‘glorify war – the only cure for the world,’ exhibiting ‘militarism, patriotism [...] and contempt for women’. Thus, a queer space-time – ‘nonlinear, antifamilial, nonreproductive, antihistorical, nonnormative, anachronistic’ - is key to H.D.’s cultivation of ‘new forms of resistance and enjoyment’.

H.D.’s desire to escape to an ‘elsewhere’ is understandable in face of oppressive regimes and a benumbed post-war London, the temporality of which felt like ‘so many unfamiliar and un- landmarked centuries’. ‘Time had the world by the throat, shaking and shaking,’ necessitating the creation of her own queer space-time. Space and the physicality of bodies within these spaces are tangible points in which H.D. grounds her eternality against forward-moving, linear time. Through the poetic act of remembering, an eternality is cultivated, rather than a demarcation of what is past, present, and future. By going against binarizing and segmentary linear time, H.D. chooses collectivity and variegation. Love, a universal and thus eternal theme in and of itself, drives H.D.’s creation of a space-time. Like many, H.D. hopes that an undying love can be returned to and found again and again through space and time, urging that ‘if you love me,/ love me everywhere’.

‘It is nostalgia for a lost land. I call it Hellas.’ -H.D.

‘Someone will remember us/ I say/ even in another time’ -Sappho

Chapter 1: Greece, 1920

Robert McAlmon, in his ‘Forewarned as regards H.D.’s Prose,’ wrote that H.D.’s intellect is ‘more sensitive than practical’ and ‘mumbles in stumbling through the objective world’. This may sound disparaging, but McAlmon’s awareness of the tangible focus of H.D.’s prose and poetry is not incorrect. She asks in an epic poem of hers, Vale Ave, ‘Does writing equate walking?’. This spatially oriented reverence for place found its roots in H.D.’s trip with Bryher to Greece in 1920. Ultimately, H.D. uses the ever-lasting material objectivity of land to pin together disparate Newtonian times into a singular eternality.

‘I feel we must go away next winter,’ wrote H.D. in a letter to Bryher. ‘Don’t let me slide back, into our old despair’. In post-war London, ‘nothing mattered’ and there was nothing ‘to do but wait. Listen to what? Wait for what?’. It is in the face of this sensory, temporal, and spatial stasis that Bryher promised to take H.D. to ‘a new world, a new life [...] We would go to Greece’. Padded by Bryher’s family wealth, the two companions set off to Greece in February of 1920, beginning what became a lifetime of co-traveling. Though privileged to be able to escape the stifling atmosphere of London, they did face challenges specific to their gender and queerness. H.D. had hoped to walk the sacred path to Delphi with Bryher, believing she ‘would get well’, but ‘it was absolutely impossible for two ladies alone, at that time’ to do so. Before leaving, Bryher had entered a marriage of convenience with the previously mentioned Robert McAlmon (himself not straight), which made it possible for them to travel to ‘Greece and other wild places’ in a society that considered it unsafe and unconventional for two single women to travel alone. Despite these roadblocks of societal expectations, Greece was still an integral creative and romantic refuge where the two lovers could explore, away from the prying eyes of the gossipy and incestuous London literary circles. Travelling to places divergent from ‘the world of ordinary events and laws and rules’ allowed for more unfettered and unperceived self- expression.

H.D. wrote to Bryher that, in anticipation of their trip, she dreamed of ‘the sand & sleep[ing] under the stars’ and becoming ‘at one with the poems about us’ in Greece. These ‘poems about us’ refer to the same-sex desire that the Grecian Sappho’s poetry became symbolic of. Though one cannot physically unmoor an ancient past from its temporal holdings and bring it into the present, the land of Greece that H.D. and Bryher visited was the same physical land that Sappho lived, loved, and wrote in. As two female lovers, their trip to Greece was a spiritual journey in reverence of the Sapphic heritage of the country, and an attempt to glean from the land a sense of the more fluid queer expression of the ancient Grecian past. The modernist privileging of the ‘Now’ as the peak of a teleological timeline is abolished in H.D.’s reminiscent touch towards the past. She had been influenced by archaeologists like Jane Harrison, who believed that the contemporary patriarchal culture was a descent from pre-classical Minoan matriarchal societies. Only a few years before her trip to Greece, the past broke into the present through the material form of Sapphic papyrus scraps arriving from Egypt. Further, the first translations of the poetry using pronouns that revealed the same-sex desire of Sappho only came about in 1886. H.D. thus found herself a part of a relatively recent Sapphic recovery tradition, of which she contributed to in her essay ‘The Wise Sappho’, written before her trip to Greece. In this essay, H.D. depicts Sappho’s fragmented lyrics as ‘rocks – perfect rock shelves and layers of rock between which flowers by some chance may grow’. The essay conjures up a natural world of flowers and harsh coastlines, and thus H.D. meshes the past and the present as one within the timelessness of the natural world.

H.D. was aware that ‘we need scholars to decipher and interpret the Greek, but we also need: poets and mystics and children to re-discover this Hellenic world, to see through the words; the word being but the outline, the architectural structure of that door or window, through which we are all free, scholar and unlettered alike, to pass’. H.D., in this essay on Euripides, uses spatial imagery to depict this past Hellenic world, working with universal material images rather than abstract words. Though H.D. was well-versed in ancient Greek, she preferred not to connect with Sappho through translation. Rather, H.D. intimately and somatically connected with Sapphism through the tangibility of her essay on Sappho, further engaging in what Diana Collecott called a lifelong ‘creative dialog with’ the ancient Greek poettess. In the fourth century, the Bishop of Constantinople had ordered Sappho’s poems to be destroyed, only one example of many acts of destruction based in misogyny and homophobia. In response to the lacuna of Sapphism due to a history of homophobic erasure, H.D. responds by re-creating Sappho’s world from the ground up. By depicting Sappho’s poetry as an ‘island of artistic perfection’ with ‘innumerable, tiny, irregular bays,’ H.D. places herself and the reader within this Sapphic space.

H.D. writes that when she reads ‘the fragment of a melic poet’ she feels as she did when she ‘stood on the steps of the Athenian propylaea’, thus equating tangible poetry with connection to the land. H.D. imbues her literature with the presence of space and place for H.D. Her triptych novel Palimpsest is a key example of H.D.’s use of spatiality to mesh an ancient past within her own present, thus warping linear time. H.D. published Palimpsest, dedicated to Bryher, a few years after her journey to Greece. This three-part novel explores and revisits events from her own personal life through the kaleidoscopic lens of different names, times, and places, thus knitting together a distant past and a personal present as one. Each section is set in a different time and place: 75 B.C. Rome, London during and after World War I, and Egypt in 1925. In all of the sections, forward movement and teleological narrative progress is abandoned, and the novel instead moves forward only to turn back again, accruing through repetition a variegated and palimpsestic collage of time and place.

The first section, of which this chapter is interested in, is titled ‘Hipparchia: War Rome (Circa 75 BC)’. Despite being set in Rome, the chapter is imbued with a Hellenism that parallels H.D.’s own philhellenism and connection to Greece. The main character, Hipparchia, has been exiled to Rome from her conquered Corinth. The journeys of Hipparchia and H.D. run parallel: Hipparchia, like H.D., is distant from her original homeland, and both write poetry on ‘gods, temples, [and] flowers’, admiring Sappho from a displaced country. One of the key lynchpins between H.D. and her main character, Hipparchia, is found in the character of Julia who appears near the end of the section. Hipparchia, like H.D., has fallen into a deathly illness, and the Julia character arrives as a saving grace much like Bryher did. Julia knew all of Hipparchia’s poetry ‘by heart,’ just like how Bryher had memorized all of H.D.’s Sea Garden before first calling on her in 1918. Bryher, like H.D., is one of the recurring archetypal characters of H.D.’s personally invented lore, showing up not only in the different sections of Palimpsest but also in Paint it Today, Asphodel, and other novels. Bryher is obliquely reminiscent of the androgynously female characters that appear near the end of the work, often saving the H.D. character physically and spiritually. In ‘Hipparchia,’ the narrator, in the depth of her illness, has given up on Greece regaining power ever since being conquered by Rome, ‘its cities dissociated from any central ruling’. But Julia, though Roman, has learned to ‘love Athens’ through Hipparchia’s Hellenistic poetry, and insists that Greece, ‘a spirit,’ ‘is not lost’. The place of Greece thus holds within it love, desire, and the projected hope for escape and fulfilment. For Carol Gilligan, ‘[t]he body is a homeland – a place where knowledge, memory, and pain is stored’, and thus the self (both fictional and real) is entangled with place. Though the ‘Hipparchia’ section ends ambiguously, Julia’s declaration that ‘I will come with you’ back to Greece promises companionship and togetherness through travel, revitalizing the possibility of the renewal of Grecian culture that has been lost to Hipparchia, as well as paralleling Bryher’s fulfilled promise to bring H.D. to Greece. The Bryher character saves the H.D. character by promising to bring her elsewhere, thus emphasizing the importance of place to H.D. in her life and in her works.

The past that H.D. explores in writing reverberates into her future, as H.D.’s hope to one day find ‘[her] own world’ seemed to be materializing through the act of exploring Greece with Bryher. This ‘world’ is both the ancient Sapphic Greece and a place of free Sapphic sexual expression. The ancient past is recalled through spatiality, for although Newtonian time restricts the past to the past, H.D.’s grounding in spatiality makes linear time eternal and four- dimensional. She believes that ‘we are not shadows’ but that ‘as we walk, heel and sole/ leave our sandal-prints in the sand’. Despite mortality, in understanding oneself as part of a singular material reality, intimately and eternally interconnected with the land upon which one walks, the ‘past, the future and the present’ are brought together as ‘one’. This material permanence allows for lives to be acknowledged thousands of years after they have ended. H.D. thus engages in the act of remembering by visiting Greece with her own lover as she walks in the footprints of Sappho and others.

H.D. both urges and desperately desires that life (and love, and nature) is not momentary or temporary, but that an eternality of these shared experiences reaches out ubiquitously through time. For H.D, ‘[p]oetry was to remember’, and through this method she lovingly makes eternal, through and against Time, what otherwise could have been lost. The sympathetic awareness of the past as at one with the present reminds us, as John Berger puts it, that ‘that symmetry co- exists with chaos’. H.D. may not have believed in an abstract heaven distant from earthly realities; rather, she believed in an immortality cultivated through the material permanence of earth, in which life recurs beyond death as ‘old forms in new environments’. Place is integral to remembering, rather than forgetting, and creating eternality against disparate times. H.D. and Bryher may have been ‘two women alone’ on their trip to Greece, but in this eternal and everlasting continuum of past, present, and future that H.D. creates out of the (literary and physical) space of Greece, ‘[they] were not alone’.

Chapter 2: Egypt, 1923

‘...and you know queer things do happen in these old temples.’ -H.D.

H.D.’s trip to Egypt in 1923 with her mother and Bryher coincided with Howard Carter’s excavation of King Tutankhamen’s tomb, an archeological disinterment that queered linear time by tangibly bringing the ancient past into the same space as the present. For H.D., the tomb and the objects inside it had attained ‘a cryptic power’ by their ‘sheer permanence’ throughout the eons, spurring her fictional re-working of this experience in the final section of Palimpsest, titled ‘Secret Name: Excavator’s Egypt (circa A.D. 1925)’. This chapter of the dissertation will look at how H.D. treats Egypt to create an eternal space-time, as well as how this intersects with her queerness. Like the first chapter of Palimpsest, ‘Secret Name’ has another H.D.-parallel character, here named Helen, as well as several love interests: an army officer named Rafton and a girl named Mary. Egypt comes to mean a complex variegation of meanings and images for H.D., but above all it, it becomes a place of spatial fluidity for H.D., thus enabling this queerness.

The destabilizing of segmented linear time is one of the central aspects of fluidity that H.D.’s representation of Egypt exhibits. In Palimpsest, there is a strange merging of past and present in the space of King Tutankhamen’s tomb, with the sense that the ‘gilt of the tiny palace room was as if laid on yesterday by some skilled quattrocento craftsman’. Palimpsest evokes its title through the layering of times on top of one another, thus destabilizing chronological time through its temporal meandering between past, present, and past again. For the narrator, the walls of the ruins not only remind her of something ‘masonic, Roman,’ but also ‘like some heavy foundation that workmen in a New York thoroughfare had left for the noon hour’. H.D. creates a striking congregation of places in her texts, using familiar urban mundanity to describe the ancient wonders of the world to make the past at one with the present. By merging past and present as one through spatial contrast, H.D. creates her eternal space-time. H.D. (and the characters reminiscent of herself) comes to grasp this eternality through her physical connection to the land, with the ‘very dust’ that Helen stands on being the same ‘dust that for four thousand years had lain’ in Egypt and ‘still lies on the highroads’.

H.D.’s figuration of space in Egypt differs from her representation of Greece. In Palimpsest's depiction of Egypt, she brings in the landscapes of her American childhood to serve as contrast or simile to the Egyptian vistas. Like H.D., Helen is an expat from America, and while Egypt is completely new to her, it is simultaneously ‘very home-like, very familiar’. Throughout ‘Secret Name,’ place is compared to place: the buildings surrounding the roadway in Egypt remind the narrator of ‘low San Francisco bungalow residences,’ and she tells Rafton that the ‘incurve of sand about these sphinxes’ reminds her of a childhood spent ‘along the gigantic stretches of New Jersey’ beaches. The repeated reminiscing on personal place-based memories again ties place to self, H.D. self-identifying as ‘a very between-worlds person’. An amalgamation of places and times is created, and the H.D.-narrator situates herself somewhere within it. This image of self, built through a collage of places, is fluid instead of static, and unfastened from one singular place; rather, it is metaphysically somewhere between the jagged coastlines of Maine and New Jersey, London, and the sand-strewn valleys of Egypt. H.D. works with the plenitude, rather than scarcity, of time and place. Dipesh Chakrabarty defines postcolonial temporality as ‘a plurality of times existing together,’ and thus H.D.’s space-time attempts resistance towards imperializing forces. In H.D.’s space-time, ‘all planes were going on, on, on together’, and ‘the present and the actual past and the future were (Einstein was right) one’.

In her denial of essentialist binaries or singularities, H.D. embraces fluidity and plenitude, which parallels her own sexual queerness. H.D. identified as bisexual, aided by Freud’s identification of her as ‘the perfect bi’. The endlessly fluid accretion of times and places parallels Hélène Cixous and Catherine Clément’s understanding of bisexuality in The Newly Born Woman, which Sean Richardson summarizes as ‘as a fluid pluralization of desire that refuses to be confined or fixed’. For Helen (and thus H.D.), Egypt offered freedom ‘from maternal, fraternal or paternal solicitudes’ and other ‘restrictions’, like heteronormative expectations of a domestic, familial and (re)productive life plan. Though Helen worries that the English captain she has been flirting with ‘should think her “queer”’, fortunately, ‘queer things do happen in these old temples’. The fluidity of time and space in H.D.’s representation of Egypt thus allows for her queerness, and Helen eventually gives up on her ‘paper-doll’ performance for Rafton and embraces her desires. The partitions of ‘self carefully guarded [...] had been broken in the magic of this atmosphere’, allowing the queerness of the relationship between Helen and Mary to be expressed in relatively explicit terms. Mary muses on marrying a boy called Jerry, and Helen despairingly wishes against their marriage. But, struck silent by the power of heteronormativity, Helen cannot find the words to ‘translate the code of her heart tap and beat into words’; even if she could, ‘she had no courage to voice the words,’ and she muffles her queer longing. But as ‘Secret Name’ progresses, Helen experiences increasing freedom, and the intimacy between her and Mary is described in spatial terms, the two merging ‘almost without [...] partition of personal self.’ Through the material rhetoric, the narrative comes to term with Helen’s queer identity. Ultimately, the fluidity of Helen’s desire is boundless while in Egypt, oscillating between Mary and Rafton. She resists binaries (which always work ‘to the advantage of certain (dominant) social groups’) and instead exists as many things as once, much like the variegating plenitude of times and places within Palimpsest.

It is necessary to contend with the colonialist exploitation of Egypt and its ancient past that underpins aspects of H.D.’s representations of Egypt. The excavation of the tomb coincided with Egypt gaining partial independence from British rule, leading to a rise in nationalist pride, coined Pharaonism, for the country’s ancient history and ruins. Tensions increased between Egyptians and British-led archaeology teams over who should have ownership of the newly discovered tomb of King Tutankhamen, and Howard Carter faced backlash for entering the tomb before notifying the Egyptian-founded Antiquities Service. Fikri Abaza wrote in al-Ahram, one of the main Egyptian newspapers, that Lord Carnarvon (the financial backer of the excavation), was ‘exploiting the mortal remains of our ancient fathers before our eyes, and he fails to give the grandchildren any information about their forefathers’. And certainly, well-off travelers like H.D. were benefitting more from the excavations of the tomb than the Egyptian ‘grandchildren’ of the Pharaohs were. Though Egypt figures in H.D.’s work as a place in which she can explore her fluidity and queerness, it is still being used for her own ends. Egypt is figured in her work as an empty canvas on which she plays out her internal enlightenment and can act on queer desires. In reality, Egypt is a place much more than H.D.’s personal interpretation of it, as all places are fraught with questions of independence, ownership, and power. H.D. is writing its story without hearing their own narrative, and in this way, she is part of the Western imperialist hegemony that she is trying to escape.

This exploitative approach should not and cannot be ‘solved’ out of Palimpsest, but it does exist alongside H.D.’s resistance to other forms of hegemonic power, like heteronormativity. In another autofictive novel, Paint it Today, H.D. compares her relationship with Ezra Pound to the careless exploitation of tomb excavation. She feels that she ‘gained nothing from him but a feeling that someone had [...] banged on a temple door, had dragged out small curious, sacred ornaments, had not understood their meaning’ and had left them ‘exposed by the road-side, reft from their shelter and their holy setting’. She seems here to grasp the sacrilegious problematics of the Western excavation of a non-Western tomb. Russell West- Pavlov argues that absolute time, in its service to capitalism and its ‘separation of space and time is a vital actor in the subjugation of colonial territory and its people’. Thus, her depiction of Egypt, a recently independent nation, as fertile to her broader queering of time is problematic and simultaneously resistant to exploitative forces of temporality.

With time and space free from its constraints of linearity and essentialism, and instead always interrelated to other times and places, there is a similar freedom found within the characters. H.D. urges a fluidity and collectivity through her space-time that is central to breaking down binary demarcations such as ‘present’ versus ‘past’, or the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ that propagates imperialist aims. H.D. is interested in what is ‘eternal’ and ‘undeviating,’ denying determinist beginnings and ends. This allows singular and hegemonic narratives to be re-written and re-worked, much like how she re-wrote the story of Helen of Troy in her Helen in Egypt. Helen of Troy had been written into the mythical roots of misogyny and had ‘withstood/ the rancour of time and hate’. Here linear passing time is clearly something destructive, interdependent on misogynistic and patriarchal hegemons. H.D. offers an alternatively fluid and eternal temporality that allows for the re-writing of a past previously believed to be set in stone.

Chapter 3: Vienna, 1933-1934

‘All moments past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance.’ -Kurt Vonnegut

On and off from 1933 to 1934, H.D. went through intensive psychoanalytical sessions with Sigmund Freud in Vienna, Austria. She had reached out to Freud, at this point already a well-known figure, after enduring a nervous breakdown that affected both her daily life and creative output. She charts her time in Vienna in diary-like entries in her only published non- fiction novel, Tribute to Freud. H.D. uses a free indirect discourse that ignores linear teleology and instead moves fluidly between connections, a prosaic style that is reminiscent of Freud’s psychoanalytical method of free association. Though H.D. developed a close relationship with Freud, she understood that he was ‘not always right’, and certainly, many of Freud’s theories were repressive and binarizing, as Tribute will come to show.81 Alongside Freud’s often hegemonic ideals, another oppressive force was looming in Vienna. During H.D.’s time there, the Nazis were gathering forces and beginning to encroach upon Austria. Among the places of import to H.D. explored thus far, Vienna is not figured in queer terms, but instead depicts temporality as linear and scarce, and spatiality as restricted and suffocating. While Vienna as a geographical space did not further secure H.D.’s eternal space-time, she offers an oppositional space in Tribute to Freud: the space of the mind, an intangible space made tangible through her depiction of it in fluidly oceanic terms. Against the war-time space of Vienna and the normativity of Freud’s beliefs, H.D. creates pockets of queerness and eternality through the fluidity of her depiction of space. Thus, H.D.’s representation of Vienna in her autobiographical Tribute to Freud holds within it two contradictory presentations of place that further complexifies her space-time.

Tribute to Freud is very much aware of linear clock-time. H.D.’s sessions with Freud are rigidly ordered, meeting ‘four days a week from five to six; one day, from twelve to one’. Clock-time, which Valery Rohy identifies as ‘straight time,’ is reciprocally adherent and integral to broader hegemonic practices and solicitudes. H.D.’s writing inhabits a capaciously infinite and plural time and space, and yet Freud and Vienna suffocate this expansiveness. Freud has a tight grasp on the word ‘Time [...] in his inimitable, two-edged manner; he seemed to defy the creature, the abstraction; into that one word’. With Freud always ‘keep[ing] an eye on the time,’ H.D.’s view of time as ‘a creature,’ writhing and inconsistent, is simplified and essentialized. Though Freud can be oppressive and marginalizing towards H.D, as Tribute will come to show, he also was marginalized in his own way. Freud was Jewish and therefore at great personal risk from the Nazi forces. His spatial security in Vienna was precarious, writing to H.D. in 1934 that ‘for a while [he was] afraid [he would] not be able to stay in this town and country’, and in 1938, he was forced to leave Vienna forever due to the war.

He writes to H.D. that ‘times are cruel and the future appears to be disastrous’, revealing his own peril under the subjugation of deathly linear time. Unlike Greece or Egypt, Vienna is not represented by H.D. as offering a plurality of experience and expression; rather, the space and time of Vienna is depicted as a narrowing tunnel-vision tracking towards an apocalyptic endpoint. H.D. experiences a war-time temporality that Rohy defines as ‘utterly deterministic,’ or a ‘current of inevitable events’ that swept H.D. ‘right into the main stream and so on to the cataract,’ and thus the tributaries of possibility are claustrophobically narrowed. This war- time determinism restricts time in all directions, disallowing the ‘future [...] to be different than the present’ nor the past to happen ‘differently than it actually did’. Space merges with time, not in the way of H.D.’s eternal space-time but apocalyptically, through the physical infringement of fascist forces. As clock-time ticks by, ‘the war closed on us,’ and ruination is portended by the rifles stacked in ‘bivouac formations at the street corners’. The forward- marching linearity of time - the Now and the Next - becomes inescapable, while the space of Here is constricted by soldiers and barbed wire. The spatial foreshadowing of ruin is actualized by the Nazis’ invasion of Vienna in 1938, and the city’s later demolishment by bombs. The space and time of Vienna in 1933 and 1934 as depicted in H.D.’s Tribute to Freud thus stands in contrast to her queered eternal space-time. The temporality that emerges is instead more reminiscent of Martin Heidegger’s ‘Being-unto-death,’ in which death is a penultimate event that casts a deathly pallor over a linear experience of life.

Heidegger’s death-oriented temporality works in tandem with hegemonically repressive forces (beyond the rising fascism) that H.D. experiences while in Vienna. Heidegger’s ‘Being- unto-death’ is quicker to marginalize female rather than male bodies, as the female body is deemed increasingly useless or unwanted as it ages and loses reproductive abilities. After a certain peak age, the female body is slowly depreciated in the infinite-growth complex of capitalism that urges heteronormative marriage and reproduction. The misogyny that Freud propagated is bolstered by linear temporal frameworks. Freud makes H.D. ‘feel old’ when she tells him about a younger lover of hers, and he responded, ‘”Was that only two years ago,” as if at my age (forty-six) I should be well over that sort of trifling’. The value of a woman is reduced to what her body can and cannot do, and she is either too early or too late, too young or too old. Thus, H.D., due to her gender, is refused the experience of living more freely and fluidly in time. Freud also utilizes linear temporality in order to repress other non-normative aspects of H.D., like her bisexuality. The oppressive consequences of an essentialist binary of an archaic past versus a progressed present is most evident in Freud’s understanding of bisexuality. He identified H.D. as bisexual, but saw bisexuality as a primordial, archaic sexuality that she had yet to develop out of. While H.D. connected her queerness to an ancient Sapphic past, Freud associated it with the past in order to demarcate it as non-normative. When H.D. tells Freud that she had been in love with a girl, Frances Josepha, and ‘might have been happy with her, he said, “No – biologically, no.”’. Freud delegitimizes H.D.’s sexuality, erasing it under the guise of scientific expertise, therefore emphasizing how disciplines of knowledge are used to affirm what is normative and not. But in transcribing Freud’s repression of her queerness in Tribute, she begins to undermine the totality of his influence.

In reaction to these modernist impulses of violence, misogyny, and homophobia, as well as the Nazi’s ‘threat and constant reminder of death’, H.D. was ‘forced to compensate, by memories of another world, an actual world where there had been security and comfort’. Despite the various oppressive forces in Vienna, H.D. ultimately creates a space of queerness in Tribute. Even in the space-time bounds of Vienna during these pre-war years, H.D. foregoes singular space and linear time, using the tangibility of her prose to queer space and time. In their allotted discussion times, H.D. and Freud often transversed the objective limitations of time and space, traveling ‘far in thought, in imagination or in the realm of memory’. For H.D., these ‘memories, visions, [and] dreams’ are more than abstractions; rather, ‘they are real’. Though they are in Freud’s ‘old room at Bergasse,’ when they go on ‘one of our journeys,’ they are also in ‘Italy; we were together in Rome. The years went forward, then backward’. The multifarious and oscillating movement between time and space, this ‘shuttle of the years,’ ‘ran a thread that wove [her] pattern into the Professor’s’. Not only is space and time warped, but this queered space-time also facilitates a universal human connection, weaving connections through an amalgamation of place.

H.D.’s resistance against binary, singular space and time is culminated in her depiction of the mind as an aqueous, oceanic place in Tribute to Freud. The mind space figured as a sea-like or aqueous space is not entirely new to H.D. She writes in Palimpsest of diving ‘deep, deep courageously down into some unexploited region of the consciousness, into some common deep sea of unrecorded knowledge’. In Tribute to Freud, the mind is figured in aquatically spatial terms, and this psychic ocean can be explored to find repressed memories or psychoanalytical gold. H.D. must immerse herself fully in the vast sea that is her mind, knowing she ‘must drown, [...] completely in order to come out on the other side of things’, a process that she goes through with Freud. H.D. broadens her imagery of the aqueous mind-space as an ‘unexplored depth [that] ran like a great stream or ocean underground’ and ‘the dream of everyone, everywhere’. In Sean Richardson’s work on H.D., Richardson cites Roman Rolland in a letter to Freud, equating the ‘oceanic’ with the ‘feeling of the eternal’. The oceanic mind space is thus in tune with H.D.’s broader argument of eternality. H.D. hopes to proclaim through this aqueous imagery ‘all men one,’ making the aquatic figuration of the mind connected to the ‘whole race, not only of the living but of those ten thousand years dead’. ‘[B]arriers of time and space’ are blurred and ultimately, ‘man, understanding man, would save mankind’. H.D. uses her non- essentializing eternal space-time to meet larger collective aims for humanity in the face of the violent hegemons and forces that flare up during wartime.

Valery Rohy, in her look at the deterministic historical time in Tribute to Freud, ultimately argues that H.D. is unable to offer a queer alternative time in Tribute. Yet the oceanic space is the queerest of all H.D.’s places, an utterly ubiquitous and tangibly enveloping geography. The cultural geographers Philip Steinberg and Kimberly Peters’ ‘wet ontology’ figure the sea as offering a reimagined understanding of the world ‘through its material reformation, mobile churning, and nonlinear temporality’, resisting fixity and thus inherently queer. H.D. accordingly uses the imagery of the ocean to create a queer mind space resistant to linearity and essentialism. Through the oceanic mind space, as well as her layered plurality of times and places in Tribute, H.D. expresses her desire to ‘refuse time by refusing to narrate it or resist the Nazis by resisting history itself,’ avoiding the ‘strictly historical sequence’ and creating instead a fluid, non-singular eternality. While writing the space of the mind as eternal or layering places in fiction does not fix war or saved loved ones from exile, it urges a move towards collectivity and oneness.

Against Heidegger’s fatalistic understanding of time, or hegemonic linear clock-time, H.D.’s eternality emerges in her writing through the queering of space and time. This eternality is in reaction to impending death and the urgent desire to never lose those you love. Though Freud often disseminated repressive and normative solicitudes, H.D. held a strange sort of love for him. She antagonizes over his future death, writing that if she could, she ‘would have taken the hour-glass in [her] hand and set it the other way round so that the sands of his life would have as many years to run forward as now backward’. In the face of possible death, the yearning for life to continue intensifies. She is forthright in her desire for the lives of those she loves to go on infinitely by reversing and queering time. H.D. believes that ‘the dead were living in so far as they lived in a memory or were recalled in a dream’, and they can likewise be reincarnated, in a sense, through the immortalizing power of writing. Revealed at the core of her eternal space-time is the simple yet universal human desire to resist the dominion of death, and live one more day with those she loves. Ultimately, through her eternality, H.D. urges that in ‘the face of Death,’ ‘Love is stronger’.

Chapter 4: Isles of Scilly

‘And he’s always been here in my heart before I even knew him. Understand? He’s always been here. Always.’

-Sandra Cisneros

‘I am with you... every time I go places, I am with you and re-living it all.’

-H.D. to Bryher

H.D. remembers a densely forested island in the Lehigh River during her childhood in Pennsylvania as a ‘miniature Atlantis’ and which spurred a life-long search for islands. Her proliferation of islands throughout her work, she writes, is not entirely literal, but ‘are symbols’ for a deeper ‘nostalgia for a lost land’. H.D. left America to chase after unpromised ideals, moving boundlessly from place to place, driven by this non-specific nostos. H.D. ultimately cultivates an amalgamation of places, resisting singularity and instead collecting, layering, and treasuring a variety of places and times, both through physical and literary travel. She also associates islands with finding a loved one who fulfils that endless search, which she expresses by asking, ‘What are the islands to me/ [...] What can love of land give to me/ that you have not’?

The speaker of another of H.D.’s poems asks a lover, ‘where did we come from – how did we meet here -/ where have you gone?’ This somatic desire for a lover is punctuated with questions of geographical location – ‘where,’ ‘here,’ and ‘where’ again. Love, to H.D., is understood in terms of place, a ‘somewhere’ that she can eternally shore upon. Throughout her works, islands are figured most consistently as a place of love, or a refuge from war and hegemonic subjugation. One of the most important islands of her symbolic proliferation of them was the one that Bryher took her to the summer after they first met. This dissertation thus ends where H.D. and Bryher first consummated their relationship: the Isles of Scilly. As a couple, they only went to the actual Isles once (specifically the island of St Mary), just after World War I. Though they never travelled to the Isles together after that (they planned to in 1941, in the midst of World War II), they tried, whenever possible, to meet in the nearby south of England every year for the anniversary of their meeting. The summers H.D. spent in a lush natural landscape with her lover ‘were so important to [her] body and spirit’. Traveling to an island (or surrounding mainland coasts) to escape was a privilege few could afford, and H.D. was ‘immunized and insulated from the war disaster’ in this archipelagic utopia, thanks to Bryher’s wealth from her family’s ship-owning industry. H.D. was lucky to be taken there by Bryher just after her post-war despair (losing her brother, her father, her marriage, contracting influenza and two near-death childbirth experiences). The Isles (and Bryher) changed the course of H.D.’s life for the better.

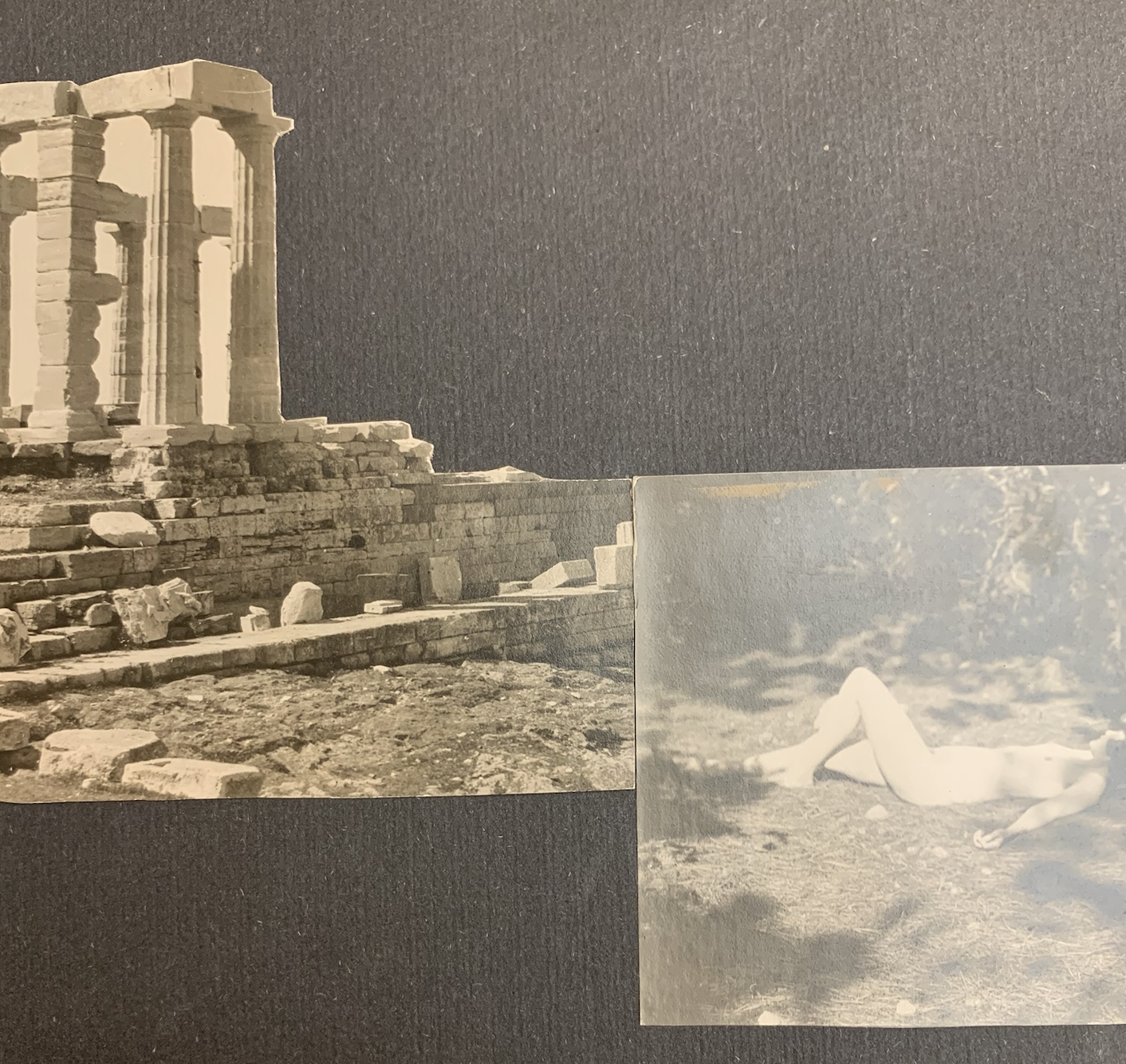

This first trip to the islands not only marked the beginning of a life-long relationship with Bryher, but it also became more broadly emblematic of H.D. finding a queer love that was creatively and spiritually fulfilling. On this 1919 trip to the Isles, the couple wrote, took turns watching over H.D.’s new daughter, explored the fecund natural world of the isles, and photographed each other naked on the rocky coasts. Though this was a one-time trip, the spatiality of H.D.’s configuration of the islands cements this space in her texts, thus eternalizing this place of queer love. In 1941 when she was too ill to travel down south with Bryher, she re- visited ‘some of the Scilly notes’ and was transported ‘back to July 1919, where we were there – about now – together’. Even when she is not physically there, the islands (and the act of being ‘together’ with Bryher) are rendered eternal through the act of reminiscence in her writing.

This chapter will be looking at several of her works, foregoing singular focus and instead embracing H.D.’s own approach of plentiful variegation, finding strands of thematic consistency throughout. However, this chapter will use as a structure her Notes on Thought & Vision, an aphoristic contemplation on creativity, the body, and the natural world. Notes was written during her first and final summer in the Isles of Scilly with Bryher, and thus is integral to a discussion of this place. The environment of the Isles is unforgettably striking, with large, strange birds flocking from both ‘the tropic zones’ and ‘the Arctic’. The flora is strangely fantastical, and H.D. and Bryher ardently explored the ‘fibrous under-water leaf and those open sea-flowers’ that ‘gave one the impression of being submerged’. The Scillies are un-fixed in their liminality between land and water, thus becoming a place of non-essentialist queerness for H.D.

H.D.’s focus on place and environment is fluidly queer, as well as connecting with a broader universal eternality. As H.D. puts forth in her works, both collectivity and eternality are made possible through spatiality. With the marine plant life of the Scillies in mind, she asks in Tribute to Freud, ‘Are we psychic coral-polyps? Do we build upon one another?’ She approaches universal consciousness and connectedness through images of the aquatic natural world, urging an autopoietic ‘myriad-minded coral chaplet or entire coral island’. Notes on Thought and Vision transcribes what H.D. refers to as her jelly-fish vision, a strange experience that occurred on the Isles of Scilly. What she gleans from the vision is the sense of ‘a cap, like water, transparent, fluid yet with definite body,’ over her body and mind. She calls this the ‘over-mind,’ and above all it is ‘a definite space,’ with ‘sea-plant, jelly-fish or anemone’ and where ‘thoughts pass and are visible like fish swimming under clear water’.

H.D. here connects the human body and mind with their environment, aligning with Henri Bergson in his belief that the ‘mind is continuous with matter, so that matter is simply the lowest state of mind and mind the highest state of matter’. The material reality of a landscape is central to H.D., which she expresses in several of her works, including her autofictive Paint it Today. Here, she writes that landscape is prominent in the creation and conception of self, for ‘language and tradition do not make a people, but the heat that presses on them, the cold that baffles them, the alternating lengths of night and day’. H.D. exhibits the theoretical idea of geographical queerness to the full extent by becoming physically at one with her surroundings. Sean Richardson argues that bisexuality works in ‘permeability and porousness’ and ‘accepts the space that surrounds it and, in doing so, becomes innately queered by geography’. In Paint it Today, H.D. urges the reader to ‘take a deep breath and be lost between thick pine trunks. The feel of it. The bite and tear and sting of it’. Jon May and Nigel Thrift write of the connection between human and natural worlds to emphasize ‘an order of ceaseless connection and reconnection... [and] networks which are circulations, rather than entities or essence’. H.D. connects body and nature within an autopoietic dialogue, creating a sense of eternality out of this collective relationship of endless creation, decay, and regeneration. These ‘ceaseless connection[s]’ evoke the eternality of a spatial earthly time and resist linear and abstract capitalist time.

At the center of this relationship between humans and landscape is the fulcrum of love. H.D. puts it simply in her poem, ‘The Dancer’: ‘I worship nature,/ You are nature,’ equating the environment with the poetic recipient of desire. Love, not excluding bodily lust, is a central element to the philosophy of Notes. H.D. urges that artists need sexual and ‘physical relationships,’ and ‘to shun, deny and belittle such experiences is to bury one’s talent’. This is expressive of H.D.’s emphasis on the importance of material reality throughout her works. When any kind of artist has been working, their ‘mind often takes on an almost physical character,’ or ‘his mind becomes his real body’. Thus, for ideal artistic creation, the body, at one with the mind, must make contact with other bodies. Like a lump of coal, the body ‘fulfills its highest function when it is being consumed,’ and the ‘body consumed with love gives off heat’. H.D. thus gleans her philosophy of Notes from the spiritual and bodily love she experiences on the Scillies, for it was ‘being with Bryher that projected the fantasy’ of the jelly-fish vision.

Land, body, and love are intertwined in a dialogic and eternally interconnected relationship with one another. H.D. brings together these multidimensional strands when she asks, ‘Where was I, if Bryher couldn’t find me?’ This question imbues the act of being in love with the idea of place and spatiality, equating her island imagery with fulfilling love. Bryher and the islands become metaphorically intertwined in H.D.’s personal poetic language, a correspondence backed by the fact that Bryher had renamed herself after one of the wildest islands of the Scillies – Bryher literally is an island. In the first section of Palimpsest, set in 75 B.C. Rome, the H.D.-reminiscent character, Hipparchia, has deemed herself ‘the one fated to recall the islands, to string them, thread them, irregular jagged rough-jewel on a massive necklet’. Hipparchia, and thus H.D., uses the medium of archipelagic (and other topographical) imagery in order to convey artistic meaning and message. Hipparchia looks into the eyes of the Bryher-like character, Julia, seeing ‘eyes that reflected islands [...] Tiny island upon tiny island’. The narration circles back repetitively to this image of eyes that ‘looked and look and islands [that] shone far and far,’ thus further revealing H.D.’s nostos and desire for refuge. In Palimpsest, the reprieve is offered by this island-like girl, who, like Bryher, promises escape to the isles with the declaration of ‘I will come with you’ – for Hipparchia, the isles of Greece, for H.D., the Isles of Scilly. The modernist era that H.D. was a part of reached such an ‘escape velocity from the gravitational pull of any grounding in reality or history such that [one was] left floating in weightless, directionless space’. Julia of Palimpsest and Bryher are both depicted as grounded and tangibly comforting refuges that ‘hard as ivory, dragged her back’ to save Hipparchia (H.D.) ‘when she was lax and floating’. The islands, and the love equated with them, are key topographical places that H.D., in the face of numb despair, searches for and finds in her poetry and her life. Russel West-Pavlov urges that ‘“Where” is always a part of us and we are a part of it’, thus making eternal the archipelagic landscape and the love associated with it. H.D.’s declaration of poetic desire to ‘stay as you are a little longer,/ stay as you are for years, for centuries’ is answered and echoed endlessly in eternity, found somewhere on an island.

Conclusion

‘For all the years that seem almost as one’

-Letter from Bryher to H.D.

Through physical or literary travel to various places, H.D. queers time, foregoing linearity and embracing eternality. Her rhetorical use of spatiality merges time with space, a four-dimensional continuum that is fluidly plentiful, moving seamlessly between times and places, rather than essentialist singularity. H.D.’s texts build touchable, material worlds and connections to those in the past, resisting the ravages of forward-moving linear temporality; rather, H.D.’s space grounds time towards it in an intimate autopoietic dialogue. Love is likewise interdependent with this space-time: the universal and timeless experience of love sympathetically bolsters eternality, and, simultaneously, the creation of eternality is rooted in the desire to immortalize a loved one beyond binaries of past and present.

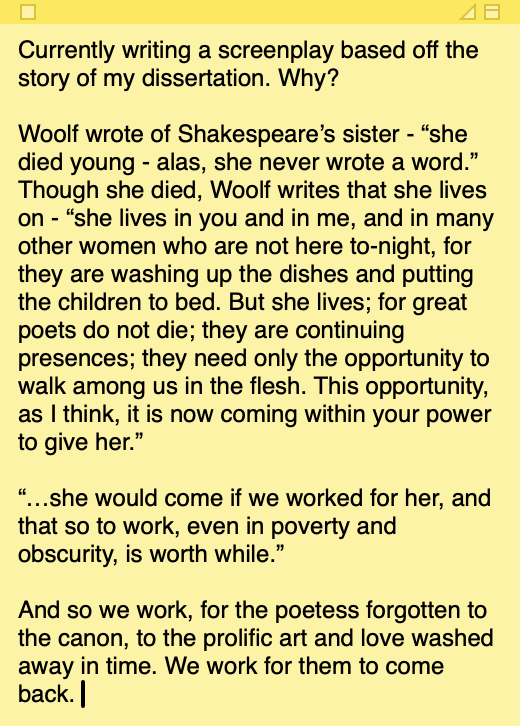

Eternality is a delicate promise in the face of the subjugation of linear time and other hegemonic forces. A collection of unpublished remnants of H.D.’s life and legacy are packed away in Yale at the Beinecke Special Manuscript Library, forty-odd boxes preserving just that uncertain immortality. Alongside thousands of letters, first drafts, and journals, Beinecke has also kept H.D.’s personal scrapbook. Leather-bound and decaying, H.D. has collaged in this scrapbook various trips, people she loves, and other cut-out images onto the black pages. Among these include images of her and Bryher nude and nymph-like, clambering over rocks on the coast of California and Cornwall. The liberty of bodies and the freedom to love one another is encapsulated in (and often restricted to) the intimate cardstock pages of a woman’s scrapbook.

Next to these images of herself and her friends and lovers, H.D. has cut out ancient Greek statues and reliefs. She places these disparate images, times, places, and people at one in the unpublished private pages of the scrapbook, merging in a queer collage space and time, past and present. Through cutting, splicing, and pasting, H.D. has done in her scrapbook what she does in her literary texts. She creates a kaleidoscopic, plentiful amalgamation of space-time, not to reveal differences through juxtaposition but to emphasize what is eternal, always, and similar (even mundanely so). H.D. looks toward the unchanging details that make up the patchwork of the human soul and body throughout time: the flowers that come back each year, the cyclical rising and falling of the tides, the sinew between the shoulder and the neck, the ancient temples that still stand, the stars above, and the feeling of a lover’s gaze on you.

H.D. confesses, ‘I do not know your age nor mine, nor when you died/ I only know your stark, hypnotic eyes’. In this time of love, hours can pool out into eternity and a lifetime can condense into one moment. Love is a request, a belief, and a hope against the plundering of linear time. Love is thus the catalyst of H.D.’s eternal space-time. Unfortunately, the body, shielded only by the hopeful assertions of poetry and prose, is not immune to death. But the tendencies of hope alone resist the erasure and emptiness of Heidegger’s ‘Being-unto-death’ and other linear-leaning temporalities. H.D. died in 1961, only a mortal human like the rest of us, but she transcends death by transcribing her own additions into the universal intertextuality of the world, sending into the void the hope that someone may read it and understand. Even where the hegemonic canon has disfigured, erased, or denied certain marginalized voices, there remains fragmented and piecemeal archival, a loving and desperate hand reaching into the past in order to re-write the present and the future. Despite the exclusivity of canon-building, H.D. retains hope, and she ‘know[s] they’ll understand’.

H.D. thus does not just merge past and present, but looks toward the future as well. H.D.’s Paint it Today was never finished, the published version ending on the hope of an alternative temporality and love – ‘Let him love today who has never loved, for tomorrow, who knows where flits the creature of his loving. (In preparation, White Althea)’. Althea was the name of the Bryher character in Paint it Today. Measured against a linear time scale, and according to hegemonic and capitalist structures, the unfinished state of this novel connotes that which is imperfect, defective, and unsuccessful. But in the eternal space-time of H.D., unfinished means the perpetual possibility of re-making oneself. And it means this love, between Bryher and H.D., H.D., and others, and love in general, is eternal – there is no stopping point, no last words.

H.D. and Bryher, after a lifetime together.